💎How to Dominate the Global Diamond Market: A case study on De Beers

A step-wise guide based on how the world's finest diamond company, De Beers strategised for success in the global marketplace.

TLDR : Diamonds have no intrinsic value. Not only are they the most common gemstone but they also weren’t valued highly till the 20th century. So how do we and why do we “value” them so much?

Let’s learn from the three-step process of De Beers, one of the most revered diamond companies in the world:

1. Capture the Supply

2. Advertise yourself

3. Face your competition

Step 1: Capture the Supply

Be a Dhirubhai

In the 19th Century, a 17 year old Englishman, Cecil Rhodes, used to have a fruitful business in South Africa. He’d bought an ice making machine and used to sell to labourers working in the sun. Around the same time a ton of diamonds were found there. Starry-eyed and packed with profits, he started buying out farmlands with potential reserves. Fast forward the story and in a couple years, our guy bought out nearly all the new Diamond Mines.

He used the profits to advance his political career. Now, he was the administrator of Zimbabwe and Zambia, which gave him control of almost all of the global diamond supply under the name of “De Beers”.

Be a Mukesh

Enter Protagonist No.2: Ernest Oppenheimer, a rival diamond producer, who essentially bought his way onto the board of directors of De Beers after Cecil’s death. By 1927, he was the chairman.

Oppenheimer’s principle was: only a limited quantity of diamonds would be sent to the market, as per the demand and would be sold through one channel. A subsidiary would buy the diamonds while De Beers would determine the price and the amount they sold for the whole year. Each producer mine would get a cut of the total.

Now now, you may ask a couple of questions. Why would distributors play along? How did they maintain this exploitative relationship? What is this called?

Distributors would have the same interests: create a scarcity of diamonds and high prices will follow. Also, They used to withhold inventory in places with low prices and used to release excess supply into markets where the price was strong enough to damage demand.

Step 2: Advertise yourself

Fool Americans

Unlike today, nobody expected a diamond ring in the 1930s. But the number of brides receiving diamond engagement rings skyrocketed to 80% in the 1990s

De Beers convinced women this is what they need in order to get engaged, that the size of diamonds was proportional to the size of love.

How did they do it?

writing (or re-writing) scenes for Hollywood movies that injected diamonds into romantic relationships between men and women

giving diamonds to movie stars to use as symbols of indestructible love

placing celebrity stories and photographs in magazines and newspapers to reinforce the link between diamonds and romance

using fashion designers to talk on radio programs about the “trend towards diamonds”

commissioning artists like Picasso, Dali, and Dufy to paint pictures for advertisements, conveying the idea that diamonds were unique works of art

Fool the countries idealizing America

They were able to replicate the same in new markets like Japan, Germany and Brazil.

Japan never had a tradition of a romantic marriage. But by depicting diamonds as a way to break away from the traditional norm, they were able to build a billion dollar industry.

Step 3: Face your competition

Cozy Governments

In the 1950s, diamonds were discovered in Siberia. This offered a threat to the De Beers supply channel. So what did they do? They were able to simply buy out the Soviet Union’s entire inventory. Too good to be true, but the truth.

It also created a joint venture with the Govt. of Botswana to tap into the country’s vast reserves. It paid off well. Not only is the deal still in place today, but there is talk of increasing the govt.’s share from 15% to 25%.

This is a stark reminder of the general disregard for social responsibility by corporates. While they may boast impressive financial statements, their actions indicate a lack of empathy for the well-being of the society at large.

Capitalism at Work

To keep its system intact, it was necessary for De Beers to control the flow of rough diamonds. The biggest risk to it was new mines selling directly to the market, bypassing it.

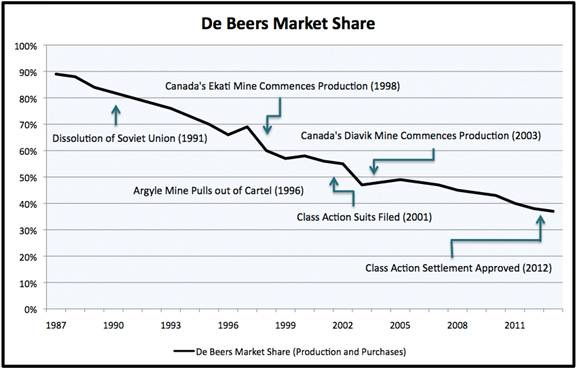

But that wasn’t how the woes started. The trigger was the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Shortly after losing control of the Russian supply, the Argyle Mine in Australia (at the time the largest diamond producing mine in the world) broke away from De Beers because of the cartels inflexibility. Over the next few years, other mines from Canada also followed suit.

In 2001, several lawsuits were filed against the company alleging that it “unlawfully monopolized” the supply of diamonds, conspired to fix, raise, and control diamond prices, and issued false and misleading advertising.” In 2012, the company ended up paying $295 Million to settle these lawsuits.

Implications?

De Beers no longer had control over the market. This was evident as in 2000, it “chose to focus” on independent marketing, leaving behind its role of the “Industry Marketer”.

They sold away a lot of their inventory (resulting in a price dip) to help with a massive company restructuring. As they continued doing this until they exhausted their industry overhang in 2005.

Overhang is a vital metric for gauging dilution and stock pressure within a company. It refers to pressure from a block of shares available for sale. A higher overhang indicates increased risk of dilution or stock pressure, making it important for investors and stakeholders to monitor.

In the following years, for the first time in a century, it was market forces that drove diamond prices.

Step 4: Moving Forward

Disrupt

In 2016, De Beers was part of an industry-wide campaign called “Real is Rare”, positioned as a counter to the growing noise about synthetic diamonds. So, it turned a lot of heads when in 2018 it launched Lightbox. Lab-grown diamonds priced so aggressively that it undercut its competitors by 7%. A classic “disrupt-yourself-before-you-are-disrupted”.

What was even more interesting was how they positioned these (relatively) low-priced gems. Boxes were clearly labeled “laboratory-grown diamonds” and were intended to be the opposite of a velvet box. Advertisements included young models in denim shirts, holding sparklers and laughing.

This was not an engagement ring, think more of a sweet 16 gift. They aimed to be a dominant player in a growing market, while simultaneously protecting the core business.

“Synthetic stones in new and fun colors, with lots of sparkle and at a far more accessible price point than existing lab-grown diamond offerings. It will be a small business compared with our core diamond business, we think the Lightbox brand will resonate with consumers and provide a new, complementary commercial opportunity for De Beers Group.” - Bruce Cleaver, CEO

Target Market? The self-purchasing professional and younger woman, the older woman who already has a jewelry collection,” and any woman “who doesn’t want the weight and seriousness of a real diamond for everyday life.

Scale

The bets have paid off. Lab grown diamonds are proving to be the fastest growing segment in jewellery. Synthetics are now found in more than two-third of jewellery stores (up from 10%, 5 years ago), their market share improved from 2% in 2019 to 10% in 2022.

While initially it only dealt in earrings and necklaces. De Beers has launched ‘Lightbox Loose Stones', where consumers can buy a stone and take it to a local jeweler to make their own rings or any dream piece. It has also amped up its technology and promises to produce “the highest colour grade, a stone can be”. These are sold under the ‘Lightbox Finest’ Brand.

Conventionally, it is difficult to meet the demand in an emerging market. But the management seems prepared. They have opened up new labs with huge capacities with a target to be able to meet “wherever demand is out there”.

They’re rightfully bullish. After all, they may have unlocked a new segment, full of frequent and repeat purchases.